Introduction

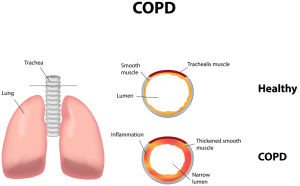

First of all, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(=COPD) is a very common lung disease, mostly caused by years of cigarette smoking.

However, it is a spectrum of lung diseases where the patient has problems breathing out. The medical language for this is “prolonged expiratory airflow”.

The lab technician measures this with spirometry. The result of spirometry shows a ratio of the FEV1, the air that is breathed out in 1 second, to the forced vital capacity of the lung (=FVC) is reduced significantly. This is understood best with flow volume curves as explained under this spirometry link. However, in simple terms it is merely important to notice that COPD patients have a permanent restriction breathing air out.

Comparison of COPD patients with asthmatic patients

Moreover, this is different from asthmatics who will have episodes with airway obstruction, but will have perfectly normal flow volume curves between attacks. Among the COPD group of patients there are two major groups represented, the chronic bronchitis patient and the emphysema patient.

Chronic bronchitis COPD patient

Furthermore, with chronic damage to the bronchial tubes the patient can have COPD of the chronic bronchitis type. For a patient to be diagnosed with this condition requires that the patient has a chronic cough (“smokers’ cough“), likewise the patient coughs up phlegm and mucous for at least 3 months in a year for at least two consecutive years. Moreover, the airway obstruction can be diagnosed using spirometry. Clinically these patients present as “blue bloaters“.

Emphysema COPD patient

Finally, when the small air sacs (alveoli) are damaged, the patient will have COPD of the emphysema type (“pink puffer“). However, there are often overlaps where both chronic bronchitis and emphysema are present and these patients are usually the ones with the most severe form of COPD.

Chronic asthmatic bronchitis COPD

In like manner, there is a minority of cases where the patient did not smoke, but had a chronic and difficult to control asthma for many years, and this type of patient can deteriorate into a COPD, which is irreversible. Notably, they have a different pattern on spirometry than the other forms and the respirologist can identify and treat such patients.

To emphasize, using spirometry the patient’s COPD can further be classified into mild, moderate or severe as is explained in this link.

Some statistics and facts on COPD

COPD is the 4th most common cause of death and accounts for 4.5% of all deaths in the US.

About 15 million people suffer from COPD in the US and about 17 million office visits are due to this lung disease. Although smoking is the most common cause of COPD, only 15% of smokers get COPD as there seems to be a susceptibility in certain people more so than others to develop it. COPD severity is proportional to the amount and years of exposure to cigarette smoke. In addition, passive smoking can also lead to COPD, but is usually less severe (Ref. 1, p. 678). Certainly, COPD affects males much more than females due to the smoking statistics in the past when males smoked much more than females. However, since females are now outnumbering male smokers in the US, the statistics are also turning around and COPD in women is now much more common.

It must be remembered that there is a strong correlation between COPD and chronic inflammation in the body (Ref. 11) and a similar strong relationship between chronic inflammation and asthma (Ref. 12).

Signs and symptoms

Above all, COPD presents itself usually in a person of 50 years or older with a 20 year or longer history of heavy cigarette consumption (more than 20 years of at least one pack per day). The patient’s main complaints are difficulties in breathing (=dyspnea), coughing up pussy mucous and periods of wheezing. In general, COPD patients cough up mucous mainly in the morning. It has a grey color to it and the patient also is also coughs it up occasionally during the rest of the day. In contrast, the patient with emphysema has hardly any mucus production, but has dyspnea with wheezing. Significantly, if the patient coughs up blood (=hemoptysis), this usually comes from chronic bronchitis or associated pneumonia.

The physician must rule out other lung diseases and heart disease

It is important to realize that the physician must rule out lung cancer. Patients with severe COPD often have symptoms of being very tired, complaining of a lack of memory, of confusion and depression. Notably, there may also be weight loss and loss of appetite because of the chronicity of the illness. Similarly, if swelling of the connective tissues (=edema) is present, this would be a pointer to a possible right sided heart failure due to pulmonary hypertension. The name for this condition is “cor pulmonale” and is a serious sign of impending deterioration of the chronic lung disease. Indeed, the physician suddenly faces a patient with both a lung and a heart condition.

Diagnostic tests

Above all, the history of breathing problems with a careful questioning of the symptoms will tell the physician already quite a lot about the COPD patient. Clinically there often is a swelling of the fingers with “watch glass nails” or clubbing. Certainly, this bulbous swelling of the finger’s distal portion develops as a result of chronic oxygen deficit in the tissues of the fingers and can also occur in the toes.

Lab tests of COPD patient

Another key point is spirometry testing that complements the clinical examination. The doctor orders chest-rays to diagnose the absence or presence of signs of severe lung emphysema. High resolution CT scans are useful in delineating emphysema, particularly, if there are small bubbles (=medically termed “bullae”). An electrocardiogram rules out a strain on the right heart, which indicates some degree of pulmonary hypertension from the chronic lung problem. The lab technician does Gram staining and possibly culture and sensitivity testing on a coughed up mucous sample (=sputum), particularly if it is pussy. Other blood tests may be ordered by the specialist to rule out allergic cells (=eosinophils) or to check for inborn enzyme deficiencies, which are rare (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency), but not infrequently seen among COPD sufferers.

Treatment

Medications

The pharmacological treatment of COPD involves the proper administration of medication utilizing the metered dose inhaler. This delivery system delivers the medications necessary to open the airways with reliability and accuracy. See this link for dosages and medication types. The American Lung Association has published this COPD fact sheet (see link) that contains a lot of useful information as well. Many COPD patients have to take corticosteroids by mouth and inhale higher doses of it as well. Patients with chronic bronchitis COPD may have to take prophylactic antibiotics on an ongoing basis such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Theophylline may be required

The physician may add theophylline and the patient has to go for theophylline blood levels from time to time to avoid toxic levels. You find a description about this also under asthma. It is advisable for the patient to attend a multidisciplinary pulmonary disease rehabilitation clinic to learn all about the various therapy steps that are necessary in concert.

Supplements for COPD patients

As mentioned above there is a strong correlation between chronic inflammation and COPD. We know from other research that fish oil (specifically omega-3-fatty acid supplements) have anti-inflammatory effects. In a study from Japan omega-3 fatty acid supplements did indeed improve the function of COPD patients in terms of increasing the walking distance in a set time interval and in terms of reduced inflammatory chemicals in the blood that led to less lung inflammation. The authors of that study concluded that it makes sense to prescribe omega-3-fatty acid supplements to COPD patients. I would add that this would be in addition to the local steroid therapy mentioned above.

Vaccinations

Vaccination against the flu every fall season and against pneumococcal infections every 5 to 6 years has been shown to be effective in preventing further deterioration and to prevent many premature deaths from COPD.

Oxygen therapy

When oxygen measurements in the blood are still deficient in severe cases despite optimal therapy with medication the doctor recommends oxygen therapy on a 24-hour basis. Dr. Lindsay Lawson (Ref. 10) pointed out that two factors determine oxygen delivery to the tissues, namely cardiac output and oxygen content of the blood. This explains why any heart disease that interferes with the pump activity of the heart will reduce tissue oxygen supply. On the other hand any problem with oxygen saturation of the blood such as anemia or slightly reduced oxygen pressure (high mountains, travel by airplane) will also reduce oxygen delivery to the tissues. Normally healthy people have no problem adjusting to the slightly reduced oxygen pressure in airplanes as the heart can automatically beat slightly faster to deliver oxygen to the tissues.

COPD patients often require continuous oxygen supply

However, in severe COPD patients this slight change of oxygen concentration in the air makes a profound difference as there can be a reduction of the oxygen saturation in the blood by 2 to 3 %. The biophysics of oxygen dissociation curves is explained in detail here for those who would like to delve into this complicated topic. These facts explain why chronic COPD patients need a continuous oxygen supply. Your family doctor can prescribe the exact oxygen concentration that such a patient needs.

Baseline tests required for insurance agencies

A baseline arterial blood gas test and possibly some other tests (spirometry, blood tests for hemoglobin concentration etc.) have to be done first. Funding agencies will require these tests as well. Portable canisters and plastic tubes and/or a mask deliver oxygen. Like other medications oxygen has side effects as well. Oxygen from a tank or canister has 0% humidity, which explains why nasal irritation from drying out mucous membranes and nasal discharge can be a problem. Sinus infections and congestions are also common. These side effects are dose dependent and one should always use as little oxygen as possible to get the therapeutic effect.

Surgery for severe COPD cases

For areas of severe involvement, particularly if bronchiectasis or emphysema is present, resection of a particularly bad affected area by a chest surgeon may be feasible. In patients with congenital lung enzyme defect a lung transplant on one lung may be prolonging life significantly. A cystic fibrosis patient with COPD may require a heart and lung transplant. The specialists involved will discuss all of this extensively with the patient and the family members. In addition the heart condition would have to be stable enough to allow such invasive procedures.

Stem cell therapy in the near future

Research has shown that stem cell therapy in humans is a feasibility. It is possible to prepare pluripotent stem cells from stem cells derived from blood and administer it through inhalation therapy with these pluripotent stem cells.

References

1. Noble: Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., Copyright © 2001 Mosby, Inc.

2. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report II. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 1997.

3. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2002, 54th ed., Copyright © 2002 W. B. Saunders Company

4. Murray & Nadel: Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, 3rd ed., Copyright © 2000 W. B. Saunders Company

5. Behrman: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 16th ed., Copyright © 2000 W. B. Saunders Company

7. Goldman: Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 21st ed., Copyright © 2000 W. B. Saunders Company

8. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.

9. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2004, 56th ed., Copyright © 2004 Elsevier

10. Dr. L. Lawson, Clinical Professor at Div. of Respir. Med., UBC, at St. Paul’s Hosp., Vancouver/BC/Canada presented “Oxygen:Diagnose, measure and prescribe”. The 50th Annual St. Paul’s Hospital Continuing Medical Education Conference for Primary Physicians, Nov. 16 – 19, 2004

11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1747070/pdf/v059p00574.pdf (W Q Gan, S F P Man, A Senthilselvan, D D Sin: Thorax 2004;59:574–580)

12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2923754/ (Jenna R. Murdoch and Clare M. Lloyd: Mutat Res. 2010 August 7; 690(1-2): 24–39)