Introduction

It is only since newer testing kits have become available in the mid 1980’s that doctors have learnt how widespread chlamydia trachomatis is.

In the U.S. chlamydia is the most common sexually transmitted infection. There is a variant of chlamydia in the tropical and subtropical areas (only rarely found in the U.S.), which affects mainly the inguinal lymph glands. It is called ” lymphogranuloma venereum”(LGV).

Signs and symptoms

In men there is a urethritis (infection of the urethra) that is caused by this bacterium. About 1 to 4 weeks after the sexual exposure there is mild pain with urination (“dysuria”).

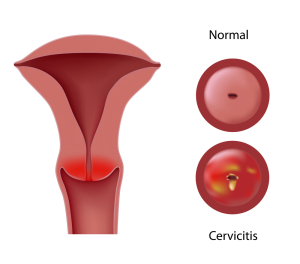

There might also be a pussy mucous discharge from the urethra, which is abnormal. The opening of the urethra on the penis can be red and inflamed. With other sexual practices such as orogenital contact pharyngitis can develop. With rectal intercourse proctitis (=inflammation of the rectal lining) can happen. In women symptoms are not as clearly defined. They may be completely asymptomatic. Or there may be a vaginal discharge, which originates from an inflammatory condition in the cervix with a pussy-mucous discharge and a reddish inflammation of the cervical lining, which expands onto the vaginally exposed outer surface. This cervical ectopy is characteristic for chlamydial infection. Other symptoms may be dysuria, pain with sex (called “dyspareunia”), urinary frequency or pelvic pain. With other than regular sexual practices there can also be pharyngitis and proctitis.

In the variant, called lymphogranuloma venereum, there is an initial blistering lesion on the genitals several days after exposure to this Chlamydia strain, which dries up and is then followed by enlargement of the inguinal lymph glands.

In women the paracervical and pelvic lymph glands get enlarged, which leads to pain in the pelvic area, particularly with intercourse. The tissue in the rectal region can also be indurated. If this is not treated, then painful fistulae (duct-like connections from the infected lymph glands to the surface of the skin, to the rectum or the vagina can form and subsequently lead to swollen legs or perianal tissue (lymphangitis with obstruction of lymphatic vessels). Some of the chronically inflamed and infected tissue can lead to polyp like granulation tissue.

Diagnosis

A morning urethral swab is most likely to show under the microscope and after Gram staining that there are pus cells and some epithelial cells present, but no bacteria (if it is a pure chlamydia infection).

Specific chlamydia tests can be sent to the laboratory for positive identification with a fairly high accuracy. If other bacteria are present such as in concomitant gonorrhea, this will show up on routine cultures. It is almost the rule nowadays that there might be more than one pathogen in sexually transmitted diseases. In women cervical secretions are sent for chlamydial tests. The newer nucleic acid amplification tests are useful to increase the sensitivity of the tests both in men and women.

Chlamydia treatment

Chlamydia infection is treated with Azithromycin 1Gm once or else with ofloxazine 300 mg twice per day for 7 days. Alternatively tetracycline 500 mg four times per day or doxycyline 100 mg twice per day for 7 days can be used. If there are recurrences, a more prolonged course of tetracycline or doxycycline for 3 or 4 weeks can be employed. With the variant of lymphogranuloma venereum treatment consists of doxycycline 100 mg, which is taken twice per day for 21 days. Alternatively erythromycin is taken at a dose of 800 to 1000 mg twice per day for 21 days. There are other alternative drugs available, but patients with lymphogranuloma venereum need to be closely watched for 6 months by a clinician with experience in this type of disease to monitor for recurrences.

References:

1.The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 163.

2.James Chin et al., Editors: Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, 17th edition, 2000, American Public Health Association.

3.The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 164.

4. Feldman: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 7th ed., © 2002 Elsevier : pages 1306-1307.