Introduction

Traveler’s diarrhea is very common. Travelers often expect the same standards as at home even in areas where sanitation is not common place. Infections often start in restaurants and bars, when there are no food inspections or hygienical standards. The most common cause is E.coli (non-problematic strains). Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea occur ½ to 3 days after the traveler ingested food or water with contamination.

For prevention the traveler has to take bismuth subsalicylate suspension (at a relatively high dose of 60 ml four times daily) for it to be effective. When there is diarrhea with bloody stools, the infection experts recommend treatment with sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim (Bactrim, Sulfatrim, Septra) or ciprofloxacin (Ciloxan, Cipro) for adults. Children under 16 years are not allowed to take ciprofloxacin, but can take sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim.

Some of the common pathogens in Traveler’s diarrhea

Campylobacter infections

Several antibiotics are effective against the campylobacter bacterium (Ciprofloxacin, brand names: Ciloxan, Cipro) is used for 5 days or alternatively azithromycin (Zithromax) for 3 days. Alternatively erythromycin (Ery-Tab, PCE, Eryc, Erythromid) would also be effective. Normally it affects the lining of the gut. In complicated infections with sites other than the gut infected, sometimes up to 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy has to be given in order to prevent recurrences.

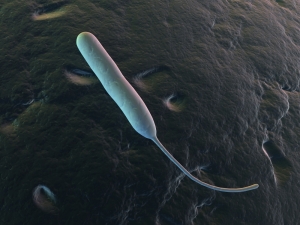

Giardiasis

The flagellated protozoan Giardia lamblia can colonize the intestinal tract and either cause flatulence, malabsorption or frank watery diarrhea. Treatment for it is metronidazole (Flagyl, Metric 21), but this cannot be given to pregnant women. A pregnant woman, however, could use the non absorbable aminoglycoside, paromomycin sulfate (Humatin).

Cryptosporidiosis

In many patients with a normal immune system this form of gastroenteritis with cryptosporidium parvum is self limiting. However, in AIDS patients and in immunocompromised patients because of chemotherapy or because of immunosuppressive medication for organ transplants this form of gastroenteritis could become a major problem with frequent and large watery bowel movements. Paromomycin (Humatin) seems to be the most successful antibiotic for this. At least in some AIDS patients antiretroviral therapy seems to also control the symptoms of cryptosporidiosis.

Amebiasis (also amoebiasis or entamebiasis)

This protozoan form of gastroenteritis involving the parasite Entameba histolytica can be asymptomatic, can be moderately symptomatic with bloody diarrhea, but it can also be a severe illness. In this latter case the amebiasis can spread via the portal vein system into the liver, where it can produce liver abscesses. From there it can spread further through the blood stream into lungs, brain or other vital organs. The abscess can also rupture into the right abdominal cavity or the right chest cavity. By that time the patient is very sick. However, it is exceedingly difficult to diagnose this condition, which would involve CT scans, ultrasounds and special immunoassays.

Treatment of Entameba histolytica

Treatment consists of drugs like metronidazole (Flagyl, Metric 21), emetine or dehydroemetine in combination with chloroquine. The gastroenterologist likely will know of newer agents that he would use for this serious condition. When treatment is finished there should be follow-up stool examinations at 1, 3 and 6 months to ensure that treatment was effective.

Cyclosporiasis and Isosporiasis

These more rare protozoans that can be a cause for gastroenteritis have come more into the forefront because of AIDS patients who can have problems with ongoing gastroenteritis involving these parasites, whereas people with a normal immune system have no or very little symptoms. Sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim (Bactrim, Sulfatrim, Septra) is effective for both of theses parasites. There are alternatives, if a person is allergic to this antibiotic.

Microsporidiosis

This protozoan called microsporidia can cause severe diarrhea in immunocompromised patients such as AIDS patients or cancer patients on chemotherapy. This protozoan can migrate from the bowel wall to the liver and produce hepatitis, also cause infection of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis) and infection of the bile ducts (cholangitis). Other frequently infected organs can be the muscles (myositis), kidneys, gallbladder, sinuses and the outer eye (keratoconjunctivitis). None of the treatments are curative, but albendazole has been reported to have a partial controlling effect and fumagillin eyedrops and fluconazole or itraconazole have been somewhat successful for the eye involvement.

Hookworm

About 25% of the world population is infected with the hookworm. There are different subtypes. The Necator americanus is the hookworm that is prevalent in the Southern United States, in Central and Southern Africa. The other widely distributed hook worm is called Ancylostoma duodenale. It is mainly found in the Mediterranean, Japan, China ,India and parts of South America. Colicky abdominal pain, flatulence and diarrhea are found in these patients. Weight loss, an iron deficiency anemia and an allergic white blood cell picture (eosinophilia) are other features. Treatment consists of mebendazole (Vermox) for three days with a cure rate of almost 100%. Pregnant women are not able to take this, but there is alternative medicine available for them. Ask your doctor.

Treatment of Traveler’s diarrhea

Treatment for Traveler’s diarrhea has to be individualized. See your doctor as stool samples may have to be sent. Depending on what the severity of the symptoms and what the underlying pathogen is the treatment may vary a lot. Fluid loss needs to be replaced. Prevention of further infestation needs to be watched for.

References

1. M Frevel Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Sep (9): 1151-1157.

2. M Candelli et al. Panminerva Med 2000 Mar 42(1): 55-59.

3. LA Thomas et al. Gastroenterology 2000 Sep 119(3): 806-815.

4. R Tritapepe et al. Panminerva Med 1999 Sep 41(3): 243-246.

5. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapters 20,23, 26.

6. EJ Simchuk et al. Am J Surg 2000 May 179(5):352-355.

7. G Uomo et al. Ann Ital Chir 2000 Jan/Feb 71(1): 17-21.

8. PG Lankisch et al. Int J Pancreatol 1999 Dec 26(3): 131-136.

More references

9. HB Cook et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000 Sep 15(9): 1032-1036.

10. W Dickey et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 March 95(3): 712-714.

11. M Hummel et al. Diabetologia 2000 Aug 43(8): 1005-1011.

12. DG Bowen et al. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Sep 45(9):1810-1813.

13. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999.Chapter 31, page 311.

14. O Punyabati et al. Indian J Gastroenterol 2000 Jul/Sep 19(3):122-125.

15. S Blomhoff et al. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Jun 45(6): 1160-1165.

16. M Camilleri et al. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000 Sep 48(9):1142-1150.

17. MJ Smith et al. J R Coll Physicians Lond 2000 Sep/Oct 34(5): 448-451.

Further references

18. YA Saito et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Oct 95(10): 2816-2824.

19. M Camilleri Am J Med 1999 Nov 107(5A): 27S-32S.

20. CM Prather et al. Gastroenterology 2000 Mar 118(3): 463-468.

21. MJ Farthing : Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 1999 Oct 13(3): 461-471.

22. D Heresbach et al. Eur Cytokine Netw 1999 Mar 10(1): 7-15.

23. BE Sands et al. Gastroenterology 1999 Jul 117(1):58-64.

24. B Greenwood-Van Meerveld et al.Lab invest 2000 Aug 80(8):1269-1280.

25. GR Hill et al. Blood 2000 May 1;95(9): 2754-2759.

26. RB Stein et al. Drug Saf 2000 Nov 23(5):429-448.

More references

27. JM Wagner et al. JAMA 1996 Nov 20;276 (19): 1589-1594.

28. James Chin, M.D. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 17th ed., American Public Health Association, 2000.

29. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 157, page1181.

30. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., Copyright © 2001 Mosby, Inc., pages 976-983: “Chapter 107 – Acute Abdomen and Common Surgical Abdominal Problems”.

31. Marx: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 5th ed., Copyright © 2002 Mosby, Inc. , p. 185:”Abdominal pain”.

32. Feldman: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 7th ed., Copyright © 2002 Elsevier, p. 71: “Chapter 4 – Abdominal Pain, Including the Acute Abdomen”.

33. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.