Introduction

This parasite infestation is also known under the name “bilharziasis”.

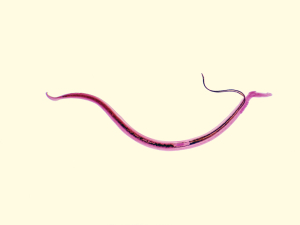

It is a form of blood fluke that multiplies in the intestine, then migrates through the blood stream to the liver and into the genitourinary tract. There is a complex life cycle that the parasite undergoes. The worms live in the veins of the bladder and the intestines. Eggs find their way into urine and feces of the host and hatch into another developmental stage that affects water snails.

There the parasite multiplies into thousands of cercariae, another larvae form of the parasite. These are released into the infested water and can penetrate human skin within minutes. The parasite transforms into another form and finds the veins of the bladder and intestines where the worms develop. It takes about 1-3 months between the point where the cercariae have punctured the skin and the stage when the first eggs appear in the urine and feces.

The worms can live for several years, perhaps even for several decades. There are different types of schistosomiasis pathogens as shown here.

Common schistosomiasis strains

| Name of pathogen: | Distribution: | Comments: |

| Schistosoma haematobium | all of Africa, also in the Middle East and India | affects the genitourinary system |

| Schistosoma japonicum | in China and the Philippines | intestinal and causes cirrhosis of the liver |

| Schistosoma mansoni | all of Africa, Brazil, Venezuela, Surinam, most of Caribbean | intestinal and causes cirrhosis of the liver |

| Schistosoma intercalatum | in Central Africa | intestinal disease |

| Schistosoma mekongi | in Cambodia and Laos | intestinal disease |

The disease does not occur in the US and Canada as the snails that transmit the pathogen are absent in the North American lakes, in other words the life cycle chain for the pathogen is incomplete. However, immigrants and travellers from endemic areas can import the pathogen in their bodies in a stable phase.

Signs and Symptoms

In travellers who have never been exposed to schistosomiasis the reaction is more acute than in someone who previously was exposed to this disease and has partial immunity.

With acute schistosomiasis there is a sudden fever and chills, the patient feels unwell and experiences muscle aches. Abdominal pain and nausea are common and allergic skin rashes as well There is a blood cell response of allergic white blood cells, called eosinophils,which typically are found with parasites. In chronic schistosomiasis there is a response of the patient to the eggs implanted in the tissue. Bloody diarrhea is found in S. mansoni and S. japonicum cases as abscesses and ulcerations in the intestinal ulcers bleed.

As the eggs of this species end up in the liver, granulomatous tissue reaction develops and leads to a nodular cirrhosis with blocking of the portal veins. This in turn leads to ruptured esophageal veins and vomiting of blood. But it also can lead to shunting of blood to lung veins and the development of pulmonary hypertension and right heart muscle strain (“cor pulmonale”). Some of these patients will develop a heart attack in the right heart chamber, although normally heart attacks occur in the left heart chamber.

With S. hematobium ulcerations in the bladder wall develop, which cause blood in the urine, painful and frequent urination and often superinfection with bacteria. Chronic granulation tissue in the ulcerations leads to a chronic cystitis (=bladder inflammation) and to stricture development in the ureters.

These strictures lead to a ballooning of the kidney on the affected side (hydronephrosis) and eventually kidney failure. Polypoid masses in the bladder, which originated from chronic granulation tissue have a high bladder cancer rate the longer they persist.

Diagnostic Tests

Urine and feces can be examined for eggs of the Schistosoma species (S. haematobium shown here). At times this may be difficult and then concentration techniques can be utilized.

When treatment is finished and tests are done to check 3 and 6 months later whether there are recurrences, antigen-detection tests can be employed. If there is a clinical impression of active schistosomiasis, but eggs cannot be proven, then endoscopic methods can be utilized with biopsies of the bladder wall or intestinal wall. Histological examination of the specimen will often show the eggs. Serum tests and titers are also useful to monitor the overall infestation and the success of the treatment. Imaging techniques such as ultrasonography and MRI scans can be useful to check state of the liver, bladder, ureters and intestinal wall.

Treatment

S. hematobium, S. japonicum, S. mansoni and S. mekongi are treated with praziquantel (brand name : Biltricide). One of the side-effects is a certain drowsiness and patients should be warned not to drive a car or operate heavy machinery on the day this medicine is taken. Only S. mansoni responds to oxamniquine (brand name: Vansil). Metrifonate, which is much cheaper in endemic areas than praziquantel is also effective against S. hematobium (Ref. 1, p. 1270).

References

1. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 161.

2. TC Dixon et al. N Engl J Med 1999 Sep 9;341(11):815-826.

3. F Charatan BMJ 2000 Oct 21;321(7267):980.

4. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 43.

5. JR Zunt and CM Marra Neurol Clinics Vol.17, No.4,1999: 675-689.

6. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 162.

7. LE Chapman : Antivir Ther 1999; 4(4): 211-19.

8. HW Cho: Vaccine 1999 Jun 4; 17(20-21): 2569-2575.

9. DO Freedman et al. Med Clinics N. Amer. Vol.83, No 4 (July 1999): 865-883.

10. SP Fisher-Hoch et al. J Virol 2000 Aug; 74(15): 6777-6783.

11. Mandell: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 5th ed., © 2000 Churchill Livingstone, Inc.

12. Goldman: Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 21st ed., Copyright © 2000 W. B. Saunders Company

13. PE Sax: Infect DisClinics of N America Vol.15, No 2 (June 2001): 433-455.

14. David Heymann, MD, Editor: Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, 18th Edition, 2004, American Public Health Association.