Introduction

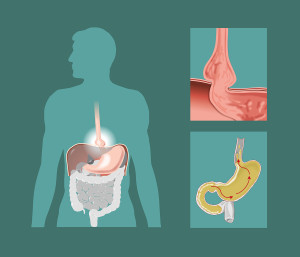

If the opening in the diaphragm is too big, then a part of the stomach can slip above the diaphragm and this is called a hiatus hernia (also called hiatal hernia). Normally the stomach is located underneath the diaphragm, which separates the abdominal cavity from the lung cavities.

We do not know whether it is from blunt trauma to the abdomen or whether it is congenital. But we know from X-ray studies that about 40% of people have a hiatus hernia (sliding type) and most do not know this as they have no symptoms.

As long as the gastroesophageal sphincter is working like a valve, the hiatal hernia will be asymptomatic. However,as the muscle fibers of the diaphragm normally wrap around the lower esophagus as well and thereby reinforce the function of this valve, it is easily understandable that in time a certain percentage of people with a hiatus hernia will eventually develop acid reflux into the lower esophagus.

Symptoms

Those patients who are symptomatic will have chest pain, sometimes indistinguishable from a heart attack. In a patient with a so called paraesophageal hiatus hernia, where the gastroesophageal sphincter is in the normal location but a part of the stomach is adjacent to the esophagus above the diaphragm, may suddenly become highly symptomatic.

A certain percentage of these patients unfortunately develop an incarcerated hernia, where the stomach that’s above the diaphragm gets stuck, swollen and then strangulates as the blood vessels get obliterated from the pressure. The patient now has excruciating pain in the upper mid abdomen, also irradiating into the chest. If the esophagus starts bleeding, there might be vomiting of blood and if this happened more slowly over a period of time there might be black stools (melena stools) from digested blood. The moment the paraesophageal hernia is incarcerated, it is a surgical emergency, as there is a danger that the stomach ruptures and stomach contents pour into the abdominal cavity leading to even a worse scenario, acute peritonitis. Any of these symptoms should prompt the person affected or a family member or friend to call 9-1-1 to get an ambulance and transport the patient to the nearest hospital.

Treatment

In the last scenario the surgeon likely will have to repair the hernia under a general anesthetic. Otherwise it is very rare that a hiatal hernia would have to be repaired surgically. Nowadays it is much more likely that either an H2 blocker or a proton pump inhibitor will control the problem of reflux and most of the hiatal hernias do not need surgical treatment.

References

1. M Frevel Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Sep (9): 1151-1157.

2. M Candelli et al. Panminerva Med 2000 Mar 42(1): 55-59.

3. LA Thomas et al. Gastroenterology 2000 Sep 119(3): 806-815.

4. R Tritapepe et al. Panminerva Med 1999 Sep 41(3): 243-246.

5. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapters 20,23, 26.

6. EJ Simchuk et al. Am J Surg 2000 May 179(5):352-355.

7. G Uomo et al. Ann Ital Chir 2000 Jan/Feb 71(1): 17-21.

8. PG Lankisch et al. Int J Pancreatol 1999 Dec 26(3): 131-136.

9. HB Cook et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000 Sep 15(9): 1032-1036.

10. W Dickey et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 March 95(3): 712-714.

11. M Hummel et al. Diabetologia 2000 Aug 43(8): 1005-1011.

12. DG Bowen et al. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Sep 45(9):1810-1813.

13. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999.Chapter 31, page 311.

14. O Punyabati et al. Indian J Gastroenterol 2000 Jul/Sep 19(3):122-125.

15. S Blomhoff et al. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Jun 45(6): 1160-1165.

16. M Camilleri et al. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000 Sep 48(9):1142-1150.

More references

17. MJ Smith et al. J R Coll Physicians Lond 2000 Sep/Oct 34(5): 448-451.

18. YA Saito et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Oct 95(10): 2816-2824.

19. M Camilleri Am J Med 1999 Nov 107(5A): 27S-32S.

20. CM Prather et al. Gastroenterology 2000 Mar 118(3): 463-468.

21. MJ Farthing : Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 1999 Oct 13(3): 461-471.

22. D Heresbach et al. Eur Cytokine Netw 1999 Mar 10(1): 7-15.

23. BE Sands et al. Gastroenterology 1999 Jul 117(1):58-64.

24. B Greenwood-Van Meerveld et al.Lab invest 2000 Aug 80(8):1269-1280.

25. GR Hill et al. Blood 2000 May 1;95(9): 2754-2759.

26. RB Stein et al. Drug Saf 2000 Nov 23(5):429-448.

27. JM Wagner et al. JAMA 1996 Nov 20;276 (19): 1589-1594.

28. James Chin, M.D. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 17th ed., American Public Health Association, 2000.

29. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 157, page1181.

30. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., Copyright © 2001 Mosby, Inc., pages 976-983: “Chapter 107 – Acute Abdomen and Common Surgical Abdominal Problems”.

31. Marx: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 5th ed., Copyright © 2002 Mosby, Inc. , p. 185:”Abdominal pain”.

32. Feldman: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 7th ed., Copyright © 2002 Elsevier, p. 71: “Chapter 4 – Abdominal Pain, Including the Acute Abdomen”.

33. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.