With the present Ebola virus (EV) epidemic in West Africa it is important to keep things in perspective. Like with any other viral illness health care provider needs to concentrate on where the virus comes from. What are the natural hosts, what transmits the Ebola virus, what is the infectious cycle? And how can the physician interrupt this cycle?

Natural reservoir

Extensive research has shown that local fruit bats that are acclimatized to live in Western and Central Africa are harboring the virus without getting sick from it. As this link points out, transmission of the virus is possible to monkeys and to humans. It is important with regard to maintaining an epidemic that the natural reservoir stays stable. In the US these very specific African fruit bats do not exist. This makes it very difficult to maintain a reservoir for the EV to multiply in North America.

Transmission of Ebola virus

Fruit bat feces contain EV particles and transmission to monkeys or humans occurs by skin contact. EV does not transmit through air, water or food. Body fluids like blood, vomitus, stool and sweat (particularly in clothing, bed sheets etc.) from a patient infected with EV can transmit EV to another person. Semen, vaginal fluid, breast milk and urine were also positive for EV when physicians tested these materials from patients with Ebola infection. Any contact with these body fluids is dangerous. Skin cells take up the virus where it multiplies and discharges itself into the bloodstream. There it paralyzes the immune system and causes severe immune suppression. The virus then infects the major organ systems.

It is interesting to note that only 16% of household contacts of proven EV patients came down with EV disease. People living in the same home who did not get in contact with body fluids of EV patients did not come down with EV disease. Those who came into contact with EV patients and their body fluids had a 3.6-fold higher risk of coming down with EV disease. Family members who touched an EV patient in the late phase had a 2.1-fold higher risk of getting EV disease. The risk from direct skin contact is lower than contact with body fluids listed above.

Ebola subtypes

Ebola has 5 different species with different mortalities. Zaire Ebola virus (ZEBOV), which was first identified in 1976, is the most virulent and the strain of the present epidemic in Africa. It has a mortality rate of up to 85% without proper intravenous fluid replacement, but with supportive measures the mortality drops to about 50%. The other species of EV are Sudan Ebola virus (SEBOV); Tai Forest Ebola virus ((TAFV, formerly called Ivory Coast Ebola virus); Ebola-Reston (REBOV) that originated from the Philippines; and Bundibugyo Ebola virus (BEBOV), the most recent species discovered (in 2008). ZEBOV, SEBOV and BEBOV were the three strains that researchers identified with large outbreaks in Africa since 1976.

Symptoms

Early signs are a fever with flu-like symptoms, joint and muscle pains, diarrhea, headaches, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Less common are a sore throat, bleeding and skin rashes. Four to five days after onsets of the EV disease hemorrhagic symptoms are in the forefront like nose bleeds, bleeding gums, vomiting of blood, black stools from bleeding into the gut, vaginal bleeding and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis (blood from under the eyelids). In addition patients may also have pharyngitis, oral or lip ulcerations. If the disease does not stabilize, liver damage, kidney damage and bone marrow cell depletion occur with an acute deterioration of the condition.

Complications of Ebola virus infection

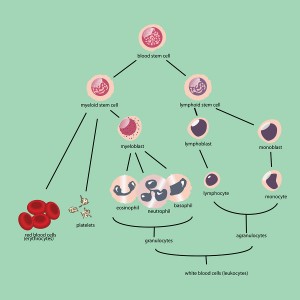

Liver failure can lead to liver coma with unconsciousness; kidney failure very quickly leads to extreme weakness with blood in the urine and uremia, which can also lead to a coma and death. Infections of the bone marrow lead to platelet and white blood cell suppression with bleeding problems and paralysis of immune responses against EV.

Diagnostic tests

After a few days of contact with an EV patient when symptoms are just starting to occur blood tests can give more information, whether the patient has been infected or not. The physician can order an ELISA test specific for EV. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR test) is also available, which detects EV more directly. Later in the disease process the physician orders an IgG and IgM antibody test. This proves the presence or absence of EV.

Treatment for EV

It is in this context that a new experimental antibody, called ZMapp has saved lives. If the physician cannot restore liver, bone marrow and kidney function by ZMapp, the patient has no hope of survival as the virus simply multiplies in these vital organs in the presence of immune system paralysis.

Overall 46%of patients in Africa have survived by mounting an immune response against EV, but 54% have died. The patients who survived inactivated the virus through antibodies from their own immune system. ZMapp is a group of antibodies against three surface determinants from three strains of EV which I have discussed in this blog. It appears that the possible toxicity of ZMapp is negligible in comparison to the effectiveness in treating EV. However, the CDC and FDA are still gathering data with every treatment (successful or not) using ZMapp.

Prevention of transmission

Unfortunately EV is one of the modern dangers and very real in Africa. It has the potential to be transmitted to other humans throughout the world and this is why governments around the world pay close attention to this modern viral illness. Fortunately a large body of knowledge has already been accumulated. Isolation of contacts for 21 days is a very effective way to separate EV patients from the rest of the world population who could potentially get this disease. Persons who have been in contact with EV patients, who were exposed to body fluids and who have symptoms of fever, abdominal pain or vomiting need to be treated early with ZMapp to stabilize the patient’s immune system and stop the EV replication within the body.

Different climate removes the fruit bat reservoir in North America

Fortunately climatic conditions within North America do not support populations of the African fruit bats. These fruit bats are what serves as a reservoir in Africa. We should therefore think of EV more like a tropical disease that can occasionally lead to flare-ups of human cases imported from Africa. It is not a disease to stay here or pose a threat in the future in North America, unless screening of patients arriving from African countries is neglected.

Summary

Ebola virus is an evolving story. Ebola is dependent on a reservoir of African fruit bats from which EV can branch out into wild monkeys. Food handlers and those who come into close contact with monkeys transmit the virus further into humans in Africa. Cases in other countries around the world remain sporadic. They have to originate in Africa where the reservoir of fruit bats and monkeys is present. Strict isolation techniques and close monitoring with specific blood tests keep these sporadic cases under control. This way they cannot reach epidemic proportions.