Introduction

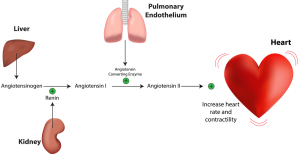

In fact, primary aldosteronism is also known as Conn’s syndrome. In this case the glomerulosa cells of the adrenal gland produce aldosterone. By all means, aldosterone is a hormone that helps to maintain blood pressure by retaining sodium in the kidney and secreting potassium into the urine. To clarify, when the kidney does not get enough blood, it releases the powerful hormone renin. Specifically, this in turn will stimulate aldosterone production from the adrenal glands via angiotensin and the blood pressure gets elevated delivering more blood to the kidney.

It must be remembered that the close feedback system between aldosterone and angiotensin is a very efficient mechanism. Unfortunately some people get a stroke from it when this mechanism gets activated with a renal artery stenosis and the patient is not aware of it. Preventative blood pressure checks will pick up such cases.

Conn’s syndrome

Specifically, Conn’s syndrome is a hypersecretion state of one of the adrenal glands due to an aldosterone producing adenoma . A histological sample was taken from a woman with a 2 cm (3/4 inch) tumor of one of her adrenal glands. Typically these aldosterone producing adenomas are located on one side only. Another key point is that in children the malignant adrenal carcinoma is more common, although overall they are rare. Otherwise, in adults the benign adenoma is more common. To clarify, if there is an adenoma in one of the adrenal glands, the Conn’s syndrome is termed “primary hyperaldosteronism”. However, there are a number of conditions that can also lead to an increase of aldosterone production, called “secondary hyperaldosteronism”. Well known conditions that cause secondary hyperaldosteronism are: cirrhosis of the liver, cardiac failure or chronic kidney failure.

Hyperaldosteronism

| Terminology: | Examples: |

| Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome) | unilateral adrenal gland adenoma |

| Secondary hyperaldosteronism | cardiac failure with edema |

| liver cirrhosis with ascites | |

| nephrotic syndrome with edema |

Symptoms

Symptoms can be very non specific and subtle. In many cases mild to moderate high blood pressure may be the only sign of Conn’s syndrome.

Due to increased aldosterone production and release there is sodium retention, which also can be measured as an increase of serum sodium. At the same time there is a hypokalemic alkalosis in the blood due to potassium depletion in the body (from urinary potassium loss). These low potassium levels lead to muscle weakness and fatigue. There can be a lack of skin feeling in some body areas, muscle shaking (= tetany) and paralysis (usually transient). Due to water retention there is also swelling of the skin (edema) and of organs internally tending to slow down their function.

Diagnostic tests

I mentioned earlier that there are certain blood tests such as electrolytes, urine tests, plasma renin levels and aldosterone levels that the doctor can order. The physician takes the blood pressure and examines for edema. With secondary hyperaldosteronism other organ functions would be assessed such as liver, kidney or heart function. A CT scan is useful to detect an adenoma on one of the adrenal glands (see arrow pointing to adenoma).

Treatment

Before the physician can treat the condition it has to be known whether there is primary or secondary hyperaldosteronism. With primary hyperaldosteronism (= Conn’s syndrome) it is important to look at both adrenal glands to be certain that there is not more than one adenoma.

If only one adenoma is present, a laparoscopic procedure may be able to remove a smaller adenoma, however in other cases the surgeon has to do the surgery as an open procedure. When a larger adenoma is present, the surgeon may have to remove the whole adrenal gland on the affected side. Fortunately the other side can adapt and make up for the hormone losses on the other side. Not all cases return completely to normal. Some cases remain hypertensive and spironolactone is then used to help normalize the hyperaldosteronism. With secondary hyperaldosteronism the precipitating other organ dysfunction has to be controlled as best as possible.

References

1. B. Sears: “The age-free zone”. Regan Books, Harper Collins, 2000.

2. R.A. Vogel: Clin Cardiol 20(1997): 426-432.

3. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 8: Thyroid disorders.

4. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 7:Pituitary disorders.

5. J Levron et al.: Fertil Steril 2000 Nov;74(5):925-929.

6. AJ Patwardhan et. al.: Neurology 2000 Jun 27;54(12):2218-2223.

7. ME Flett et al.: Br J Surg 1999 Oct;86(10):1280-1283.

8. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 261: Congenital anomalies.

9. AC Hackney : Curr Pharm Des 2001 Mar;7(4):261-273.

10. JA Tash et al. : Urology 2000 Oct 1;56(4):669.

11. D Prandstraller et al.: Pediatr Cardiol 1999 Mar-Apr;20(2):108-112.

12. B. Sears: “Zone perfect meals in minutes”. Regan Books, Harper Collins, 1997.

13. J Bain: Can Fam Physician 2001 Jan;47:91-97.

14. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.

15. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2004, 56th ed., Copyright © 2004 Elsevier