Introduction

Thalassemia is an inherited anemia. It is the most common among the hemoglobinopathies.

It is a microcytic, hemolytic anemia due to an unbalanced hemoglobin synthesis with a defect in one of the polypeptide chains. Adult hemoglobin (called hemoglobin A) consists of two polypeptide chains, called alpha and beta. But normal blood also contains less than 2.5% of hemoglobin A2, which on electrophoresis can be seen as a different, distinct line. This consists of two polypeptide chains, called alpha and delta. To make this even more complicated, there is hemoglobin F, which is the main hemoglobin during fetal growth, which has gamma polypeptide chains instead of the beta polypeptide chains of adult hemoglobin. This is important as in thalassemia hemoglobin F, which is normally present to less than 2% of the total hemoglobin, will be present to as much as 90%. Depending on which defect is present in the polypeptide chain synthesis of hemoglobin, the thalassemia is called alpha-thalassemia (defective alpha chain synthesis), beta-thalassemia (defective beta chain synthesis), etc. The most common form of thalassemia is beta-thalassemia. Thalassemia is particularly common among Mediterranean people and in people of African or Southeast Asian ancestry. Alpha-thalassemia has a more complicated inheritance pattern as there are 4 genes involved that code for this hemoglobinopathy. Defects in all 4 genes are incompatible with life and lead to a spontaneous abortion during pregnancy. When 3 genes are affected, this is called hemoglobin H disease, where alpha chain production is severely impaired.

Symptoms

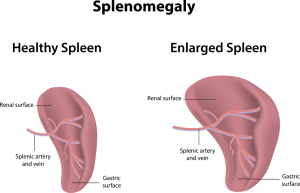

With beta-thalassemia major (the homozygous form) there will be a severe hemolytic anemia at a young age (1 or 2 years) with jaundice and iron overload. Similar to sickle cell anemia where leg ulcers and gall stones develop. There is also often a massive enlargement of the spleen (splenomegaly), where the spleen suddenly destroys and increasing amount of the circulating red blood cells. This is called acute splenic sequestration crisis. Due to the ongoing removal of red blood cells through hemolysis, there is a chronic stimulation of the bone marrow so that bone marrow develops in unusual areas such as the skull bones and the long bones. Growth impairment and pathological fractures are common and puberty can also be delayed. Heart failure at a young age can occur from iron deposits released by the decaying red blood cells or from repeated blood transfusions. Liver involvement is usual with tissue damage from iron deposits (called hepatic siderosis) and the development of liver cirrhosis with impaired liver metabolism. Patients with hemoglobin H disease have an enlarged spleen and are symptomatic with their hemolytic anemia.

The heterozygous forms of the various subtypes of thalassemia (also termed “thalassemia minor”) are often asymptomatic.

Diagnostic tests for thalassemia

With a microcytic hemolytic anemia in a person whose relatives have a history of thalassemia diagnostic tests are needed to rule this condition in or out. The standard tests for a hemolytic anemia are ordered, serum bilirubin, iron levels, ferritin, a blood smear and quantitative hemoglobin studies including electrophoresis. Hemoglobin F is determined as often this will be elevated indicating the presence of a hemoglobinopathy. A referral to a hematologist should be done as the diagnostic tests may need to be refined depending on what the exact results were. For instance, a bone marrow biopsy or bone marrow aspirate may be required. Also, liver function tests may be needed.

Treatment and prognosis

Patients with alpha-thalassemia minor and beta-thalassemia minor will have a normal life expectancy. With beta-thalassemia major life expectancy is decreased with few living to puberty or beyond. With hemoglobin H disease the outlook is dependent on the clinical course and the state of the liver and spleen. With severe splenomegaly or when the anemia is severe, a splenectomy (removal of the spleen) may be required. It may also reduce the amount of transfusions required. With children who have beta-thalassemia major as few transfusion as possible should be give to avoid iron overload. However, for children who have severe anemia a certain amount of transfusions may be beneficial to suppress the abnormal blood cell formation of the bone marrow. An ongoing chelation therapy program will prevent the toxic effects of excess iron on heart and liver by removing it. Stem cell transplantation has been done successfully in a few cases, but this is complicated by finding the right histocompatibility match, the mortality of the procedure (about 5 to 10%) and the need for ongoing surveillance of the immune system (immunosuppressive therapy) following the procedure. Eventually gene therapy will likely be developed.

References:

1. Merck Manual (Home edition): Anemia

2. Noble: Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., Mosby Inc. 2001

3. Goldman: Cecil Medicine, 23rd ed., Saunders 2007: Chapter 162 – APPROACH TO THE ANEMIAS