Introduction

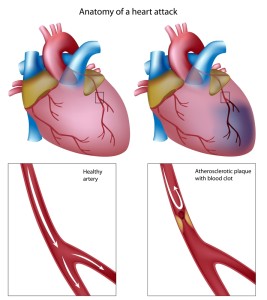

A heart attack (or myocardial infarction) is one of the ways how acute coronary syndrome (ACS) can present. Other ways are by developing angina, where chest pain occurs intermittently without injury to the heart muscle. In all cases there is a lack of nutrition and oxygen supply to the mitochondria of the heart cells. Heart muscle cells are stuffed with mitochondria, our energy providers. When mitochondria die, heart cells die. This happens when you have a heart attack. With angina pains the mitochondria are strained, but they are recovering again until sometime in the future there is a risk that they may die.

Typically a heart attack is recognized by acute chest pain that may radiate into the left arm. However, instead of chest pain the patient may have abdominal pain abdominal pain instead, especially if a posterior wall MI or an inferior wall MI is present. Once the hardening of the coronary arteries affects two or three branches, parts of the heart muscle will die off and be replaced with scar tissue. There are blood tests that will measure the release of cardiac enzymes as heart muscle cells die. These test results will establish whether or not a heart attack (MI) has occurred.

There has to be a combination of symptoms of ischemia on the one hand with at least one of the following: a pathological Q wave on ECG, ischemic changes on ECG (T wave or ST changes) or a proven significant lesion is detected during a heart catheterization (Ref. 10). According to the European Society for Cardiology and American College of Cardiology (ACC) heart attacks are now classified by the findings on the ECG at presentation in the Emergency Room, as either ST elevation MI (STEMI) or non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI). This has practical implications of management as will be explained below.

When part of the heart muscle dies, there are several consequences from this: First, there is “pump failure” because the heart has no longer the full pumping power. Secondly, there is an immediate danger of developing irregular heartbeats (arrhythmia) leading to cardiac fibrillation and death. This can be monitored for and treated with antiarrhythmic drugs (such as Lidocaine) in the Coronary Care Unit of a hospital.

The single most effective way to cut heart attack risk is to quit smoking. This link is a summary of many studies that have shown that cigarette smoking is not only causing heart attacks, but also blockage of the arteries to both legs, strokes, and breathing problems (COPD, lung cancer). So the single most effective way to prevent all of this, if you still smoke is to quit smoking.

Another important observation is that supplement, particularly vitamin E an C can prevent heart attacks.

Selenium is a trace mineral that has been found to be essential in preventing heart attacks: https://nethealthbook.com/news/low-selenium-and-heart-attacks-associated/

References:

1. DM Thompson: The 46th Annual St. Paul’s Hospital CME Conference for Primary Physicians, Nov. 14-17, 2000, Vancouver/B.C./Canada

2. C Ritenbaugh Curr Oncol Rep 2000 May 2(3): 225-233.

3. PA Totten et al. J Infect Dis 2001 Jan 183(2): 269-276.

4. M Ohkawa et al. Br J Urol 1993 Dec 72(6):918-921.

5. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., Copyright © 2001 Mosby, Inc., pages 976-983: “Chapter 107 – Acute Abdomen and Common Surgical Abdominal Problems”.

6. Marx: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 5th ed., Copyright © 2002 Mosby, Inc. , p. 185:”Abdominal pain”.

7. Feldman: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 7th ed., Copyright © 2002 Elsevier, p. 71: “Chapter 4 – Abdominal Pain, Including the Acute Abdomen”.

8. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.

9. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapters 197, 202, 205 and 207.

10. Marx: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, Chapter 76 – Acute Coronary Syndrome; spectrum of disease. 7th ed. copyright 2009 Mosby, An Imprint of Elsevier

11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19891279 : Cziraky MJ, Watson KE, Talbert RL: “Targeting low HDL-cholesterol to decrease residual cardiovascular risk in the managed care setting.” J Manag Care Pharm. 2008 Oct;14(8 Suppl):S3-28; quiz S30-1.

12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23029021 : Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Nooyens AC, Kromhout D, Spijkerman AM, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Verschuren WM: “Mediterranean Style Diet and 12-Year Incidence of Cardiovascular Diseases: The EPIC-NL Cohort Study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(9)

13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20236088 :Shecterle LM, Terry KR, St Cyr JA.: “The patented uses of D-ribose in cardiovascular diseases.” Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2010 Jun;5(2):138-42.

14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19200398 : Sawada SG, Lewis S, Kovacs R, Khouri S, Gradus-Pizlo I, St Cyr JA, Feigenbaum H. “Evaluation of the anti-ischemic effects of D-ribose during dobutamine stress echocardiography: a pilot study.” Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009 Feb 7;7:5.

15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22040938 : Ferreira JC, Mochly-Rosen D. “Nitroglycerin use in myocardial infarction patients.” Circ J. 2012;76(1):15-21.

16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21530799 : Zand J, Lanza F, Garg HK, Bryan NS. “All-natural nitrite and nitrate containing dietary supplement promotes nitric oxide production and reduces triglycerides in humans.” Nutr Res. 2011 Apr;31(4):262-9.

17. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22821988 : Christou DD, Pierce GL, Walker AE, Hwang MH, Yoo JK, Luttrell M, Meade TH, English M, Seals DR. “Vascular smooth muscle responsiveness to nitric oxide is reduced in healthy adults with increased adiposity.” Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012 Sep;303(6):H743-50.