History and initial tests

Before diagnostic tests for Crohn’s disease are done, the important part for the physician is to take a thorough history as there will be many clues, which will point to the diagnosis.

The examination will likely show tenderness and fullness in the right lower abdomen and some supportive signs such as for instance red, tender nodules over the pretibial areas in the lower legs (erythema nodosum).

Further tests

X-ray studies such as a Barium enema (double contrast) will show that there is reflux into the terminal ileum and will show the changed contours of Crohn’s disease including narrowed bowel opening, irregularity of ileum, bowel wall thickening and nodularity. Another diagnostic test is to take X-rays after taking Barium by mouth and doing a small bowel follow through.

In this approach it is important that the radiologist and patient wait long enough for the barium to arrive at the last part of the small bowel (the ileum) to document the disease segment with the Crohn’s characteristics. There is a wide variety from patient to patient regarding the bowel transit time and the diagnostic success rate may be lower that way. All of these findings and symptoms point to the presence of an inflammatory bowel disease, but other more specific tests must follow to confirm it.

Colonoscopy

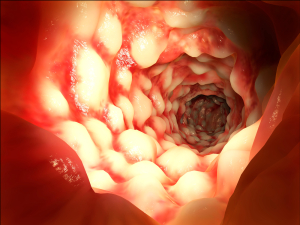

The most reliable way likely is a colonoscopy for the Crohn’s patient whose disease is in the region where the small bowel meets the colon. For the patient with gastro-duodenal symptoms a gastroduodenoscopy would be done instead. Crohn’s disease is spotty in the way it affects the bowel and some patients present with Crohn’s only in the stomach or in the duodenum. During the endoscopic procedure the gastroenterologist will take bowel biopsies, which will positively verify the diagnosis. The identifying features when examined under the microscope are focal granulomas with peri-cryptal granulomatous inflammation. In the past before a histological test it was often impossible to make a definite diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

The physician will have to be very careful to exclude other “differential diagnoses”. Those are conditions, which could present with similar symptoms, but have different causes that would be treated differently. Sometimes there might be two or three diagnoses simultaneously and each condition would have to be treated separately to help cure the patient.

References

1. M Frevel Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Sep (9): 1151-1157.

2. M Candelli et al. Panminerva Med 2000 Mar 42(1): 55-59.

3. LA Thomas et al. Gastroenterology 2000 Sep 119(3): 806-815.

4. R Tritapepe et al. Panminerva Med 1999 Sep 41(3): 243-246.

5. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapters 20,23, 26.

6. EJ Simchuk et al. Am J Surg 2000 May 179(5):352-355.

7. G Uomo et al. Ann Ital Chir 2000 Jan/Feb 71(1): 17-21.

8. PG Lankisch et al. Int J Pancreatol 1999 Dec 26(3): 131-136.

9. HB Cook et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000 Sep 15(9): 1032-1036.

10. W Dickey et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 March 95(3): 712-714.

11. M Hummel et al. Diabetologia 2000 Aug 43(8): 1005-1011.

12. DG Bowen et al. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Sep 45(9):1810-1813.

13. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999.Chapter 31, page 311.

14. O Punyabati et al. Indian J Gastroenterol 2000 Jul/Sep 19(3):122-125.

15. S Blomhoff et al. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Jun 45(6): 1160-1165.

16. M Camilleri et al. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000 Sep 48(9):1142-1150.

More references

17. MJ Smith et al. J R Coll Physicians Lond 2000 Sep/Oct 34(5): 448-451.

18. YA Saito et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Oct 95(10): 2816-2824.

19. M Camilleri Am J Med 1999 Nov 107(5A): 27S-32S.

20. CM Prather et al. Gastroenterology 2000 Mar 118(3): 463-468.

21. MJ Farthing : Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 1999 Oct 13(3): 461-471.

22. D Heresbach et al. Eur Cytokine Netw 1999 Mar 10(1): 7-15.

23. BE Sands et al. Gastroenterology 1999 Jul 117(1):58-64.

24. B Greenwood-Van Meerveld et al.Lab invest 2000 Aug 80(8):1269-1280.

25. GR Hill et al. Blood 2000 May 1;95(9): 2754-2759.

26. RB Stein et al. Drug Saf 2000 Nov 23(5):429-448.

27. JM Wagner et al. JAMA 1996 Nov 20;276 (19): 1589-1594.

28. James Chin, M.D. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 17th ed., American Public Health Association, 2000.

29. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 157, page1181.

30. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., Copyright © 2001 Mosby, Inc., pages 976-983: “Chapter 107 – Acute Abdomen and Common Surgical Abdominal Problems”.

31. Marx: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 5th ed., Copyright © 2002 Mosby, Inc. , p. 185:”Abdominal pain”.

32. Feldman: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 7th ed., Copyright © 2002 Elsevier, p. 71: “Chapter 4 – Abdominal Pain, Including the Acute Abdomen”.

33. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.