Introduction

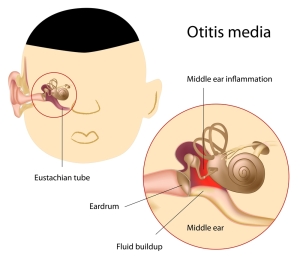

With middle ear infection, medically known as “otitis media” there is an acute infection in the middle ear. In this case it is very common in the age group of 3 months to 3 years, because the anatomy is still very tiny and the immune system is still maturing making children much more susceptible to ear infections. Generally speaking, the infection spreads from the nasopharynx area via the eustachian tube into the middle ear. In addition, second-hand smoke has been identified as a risk factor in that regard as well as the smoke irritates the lining of the eustachian tube, and the chronic swelling leads to its closure.

Infectious agents

Notably, the infectious agents are Escherichia coli (the large bowel bacterium) and Staphylococcus aureus. After one year of age E. coli becomes very rare as a cause of otitis media.

However, between the toddler age and age 15 other bacteria are common: Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, Moraxella catarrhalis. Frequently the infection will usually start as a viral otitis media, but a few days later it is often followed with a bacterial superinfection with these bacteria. In individuals older than 15 the common bacteria of otitis media are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus.

Symptoms

To clarify, otitis media starts suddenly with an acute earache, usually confined to one side. This may be accompanied with a high fever (in the order of 40.5°C or 105 °F). The patient is nauseated, may vomit and younger children may even develop diarrhea. By this time the patient is usually seen by a physician and the diagnosis is made by otoscopy (looking into the ear canal with an otoscope). The physician will see the similar picture of otitis media as depicted here.

Physical findings

Typically, the physician will see a bulging eardrum. The light reflex has been lost and the ear drum may be reddened. If the infection has been lasting for some time, there might be a perforation of the ear drum with pus and blood in the ear canal. Another complication in some cases that have been neglected, can be an accumulation of pus under pressure in the middle ear that will likely eat its way into the balance organ and cause severe dizziness and balance problems. The infection can spread to the meningeal space and cause meningitis with an acute headache and stiffness of the neck. The inner ear can get infected, in which case hearing suddenly gets lost. Other serious complications include a brain abscess and the development of a hydrocephalus.

Treatment

Certainly, any child with a fever needs to have its ears examined. If there is a history of recurrent ear infections, the ENT specialist may decide to do a myringotomy.

This is a tiny incision in the center of the eardrum. A tiny plastic tube is inserted, which falls out within 3 to 6 months, and the eardrum heals on its own. This drainage procedure usually allows the Eustachian tube to reopen itself in that period of time and when that mechanism works O.K. the danger of a renewed infection has settled down. Otherwise, the physician treats every otitis media with antibiotics, if it looks like a bacterial infection.

Viral versus bacterial otitis media

If it seems to be only a viral otitis media, the parents and the physician may decide to wait with antibiotic treatment, in case it settles down on its own. However, if it does not settle within a day or two, bacterial superinfection is likely and antibiotics will have to be started. The patient should take antibiotic medications such as amoxicillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or erythromycin for 7 to 10 days to eradicate the bacteria. A pediatrician has to treat complications in a hospital setting in case of the younger age group. For the older age group a neurologist and possibly a neurosurgeon takes care of the patient (Ref. 1, p. 673).

References

1. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 84.

2. Noble: Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed.,2001, Mosby Inc.

3. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 85.

4. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2001, 53rd ed.,2001, W. B. Saunders Company

5. Goldman: Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 21st ed.,2000, W. B. Saunders Company

6. Mandell: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 5th ed.,2000, Churchill Livingstone, Inc.

7. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 265.

8. MF Williams: Otolaryngol Clin North Am; Oct1999; 32(5): 819-834.

9. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 106.

10. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.

11. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2004, 56th ed., Copyright © 2004 Elsevier

12. David Heymann, MD, Editor: Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, 18th Edition, 2004, American Public Health Association.