Introduction

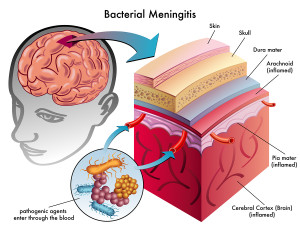

Meningitis is a serious bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic infection of the “envelope” of the brain and the spinal cord, called meningeal membranes.

The face of meningitis has changed in the last decade due to the availability of pneumococcal vaccine and haemophilus vaccine. Unfortunately, not every child is vaccinated against these diseases.

Parents have often heard unfounded rumors that the vaccines would not be effective or would be causing encephalitis. These rumors are untrue, but when the child is not vaccinated there is no protection.

Symptoms

In the beginning of meningitis the symptoms might be a sore throat and lung infection, presenting like a flu. This leads to vomiting, severe headaches, neck stiffness associated with a high fever and a sick appearance of the patient. Associated with this can be seizures, unconsciousness, even a coma in the more severe forms. In young children the neck stiffness may be missing and symptoms are more that of a sick looking child, unexplained irritability, high-pitched crying, bulging soft spot in the head in an infant (“bulging fontanelles”) with a high fever and a very sick looking child. There may also be a sudden seizure.

Treatment

An ambulance should be called and the person should be rushed to the hospital as otherwise the mortality rate is very high. In the hospital the physician will examine and likely come to a clinical diagnosis on the basis of the examination. An intravenous line will be started and blood tests including blood cultures will likely be ordered. In the case of bacterial meningitis a combination antibiotic regimen will be started rapidly to prevent further multiplication of the bacteria.

An emergency CT scan will be obtained to rule out a mass lesion in the brain. When this is excluded, a lumbar puncture is performed. With a child a pediatrician would be involved, with an adult a neurologist. Antibiotics are started before all of the final tests are in to immediately stop the toxic process in the menigeal membranes and this often will prevent deafness and blindness and permanent damage to the patient. It also makes a big difference in the survival rates of these very sick patients. Often the patient will be observed very closely in the intensive Care Unit setting in isolation to prevent spread to the other hospital patients and to protect the patient from hospital pathogens.

Special forms of fungal meningitis, of parasitic meningitis and of aseptic meningitis (from viruses) have been discussed under these links. Candida albicans meningitis and coccidioidomycosis meningitis are common in AIDS patients as their immune system is weakened. Such diseases malaria, trypanosomiasis and toxoplasmosis are examples of parasitic infestations that can lead to meningitis and central nervous system (CNS) infections.

Viral meningitis is synonymous with “aseptic meningitis” and can be caused by viral infection of the meningeal membranes from hepatitis, AIDS, hantavirus, rabies, Creutzfeld-Jacob disease and others.

References

1. Goldman: Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 21st ed.,2000, W. B. Saunders Company

2. B. Sears: “The top 100 zone foods”. Regan Books, Harper Collins, 2001.

3. The Merck Manual: Chronic Meningitis (thanks to http://www.merckmanuals.com/ for this link).

4. Noble: Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed.,2001, Mosby, Inc.

5. Goroll: Primary Care Medicine, 4th ed.,2000, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

6.Rosen: Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 4th ed., 1998, Mosby-Year Book, Inc.

7. Ruddy: Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 6th ed.,2001, W. B. Saunders Company

8. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.

9. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2004, 56th ed., Copyright © 2004 Elsevier