There are a number of hormonal changes after delivery in the mother when the baby is born.

Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid hormones, which had an increased output during the pregnancy to adapt to the metabolic challenges of pregnancy, return to the baseline production within 4 weeks from the delivery.

The actual 30% increase in size of the thyroid gland takes longer to return to the original size, namely a total of 12 weeks (Ref.18, p.693). It is during this period of time that the patient is vulnerable to develop autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto thyroiditis). For details, see link.

Ovarian hormones

Ovulation remains suppressed in most women who do not breast feed for about 5 weeks and in breast feeding mothers for about 8 weeks. However, there is such a wide variation that it is not safe to return to unprotected sexual relations. Details of contraception should be discussed among the sex partners and more information can be found under this link: birth control. 70% of women resume menstruation normally by 12 weeks when they do not breast feed. However, with breast feeding women it takes up to 3 years before 70% of them have normal menstrual periods again. This is an indirect measure of how long it can take for normal ovarian function to return.

Lactation and suppression of lactation

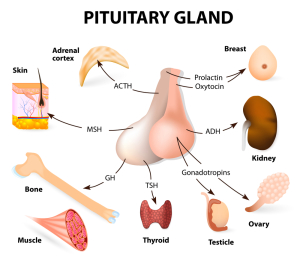

Prolactin, a pituitary gland hormone, is normally inhibited by the prolactin inhibiting factor (=PIF) from the hypothalamus. After a child is born there is a period of time where the sucking of the nipple will switch off PIF production and the breasts of the mother get transformed into lactating breasts.

Breast milk is superior to any formula as it has the right mixture of nutrients, the correct configuration of protein (human versus cow milk) including preformed natural antibodies that will protect the baby for 6 months from most common viral and many bacterial infections as well. There are only a few situations where breastfeeding is not advisable or impossible (reduction mammoplasty and certain chronic viral illnesses).

However, many women in the U.S. find it difficult to breast feed, want to feed the baby with baby formula and like to suppress the flow of breast milk. In the past this was quickly achieved with bromocriptine (=Parlodel) that was given for a period of time. As this medication inhibits the release of prolactin, it was quite popular for a number of years until serious side-effects came to be known: about 1/5 th of patients get fainting from hypotension, and experience nausea or vomiting.

Rebound lactation occurred in about 1/3 of women when they stopped Parlodel. In rare cases there were reports of heart attacks, strokes and seizures. It is because of these more serious side-effects that The Food and Drug Administration decided to no longer approve this medication for suppression of lactation. Breast engorgement and breast pain occurs only in about 40% of women who decide not to breast feed ( about 24 to 48 hours after the delivery). Care must be taken not to let the baby suck the nipples and milk should not be expressed as this would prolong the length of time it would take for the breast engorgement to subside. In most women the breast engorgement lasts for only 72 hours and the associated pain is treated with non steroidal anti-inflammatories (e.g. ibuprofen) or acetaminophen (Tylenol) (Ref.18, p.701).

References:

1. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 235.

2. B. Sears: “Zone perfect meals in minutes”. Regan Books, Harper Collins, 1997.

3. Ryan: Kistner’s Gynecology & Women’s Health, 7th ed.,1999 Mosby, Inc.

4. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 245.

5. AB Diekman et al. Am J Reprod Immunol 2000 Mar; 43(3): 134-143.

6. V Damianova et al. Akush Ginekol (Sofia) 1999; 38(2): 31-33.

7. Townsend: Sabiston Textbook of Surgery,16th ed.,2001, W. B. Saunders Company

8. Cotran: Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, 6th ed., 1999 W. B. Saunders Company

9. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2001, 53rd ed., W. B. Saunders Co.

10. Ruddy: Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 6th ed.,2001 W. B. Saunders Company

11. EC Janowsky et al. N Engl J Med Mar-2000; 342(11): 781-790.

12. Wilson: Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 9th ed.,1998 W. B. Saunders Company

13. KS Pena et al. Am Fam Physician 2001; 63(9): 1763-1770.

14. LM Apantaku Am Fam Physician Aug 2000; 62(3): 596-602.

15. Noble: Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3rd ed., 2001 Mosby, Inc.

16. Goroll: Primary Care Medicine, 4th ed.,2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

17. St. Paul’s Hosp. Contin. Educ. Conf. Nov. 2001,Vancouver/BC

18. Gabbe: Obstetrics – Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 3rd ed., 1996 Churchill Livingstone, Inc.

19. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 251.

20. The Merck Manual, 7th edition, by M. H. Beers et al., Whitehouse Station, N.J., 1999. Chapter 250.

21. Ignaz P Semmelweiss: “Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers” (“Etiology, the Understanding and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever”). Vienna (Austria), 1861.

22. Rosen: Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 4th ed., 1998 Mosby-Year Book, Inc.

23. Mandell: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 5th ed., 2000 Churchill Livingstone, Inc.

24. Horner NK et al. J Am Diet Assoc Nov-2000; 100(11): 1368-1380.

25. Ferri: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment, 2004 ed., Copyright © 2004 Mosby, Inc.

26. Rakel: Conn’s Current Therapy 2004, 56th ed., Copyright © 2004 Elsevier